Matt Breen struggles with the death of a favorite author and the threat of the Vietnam draft.

Steinbeck’s Funeral

Revolving doors spat Matt Breen into the cavernous lobby of the Wall Street office building where he worked. He tossed a few coins down at the newsstand and grabbed a copy of The New York Times. Matt rushed to catch an elevator. As it rose to his floor, he glanced at the paper. The date: Four days before Christmas, 1968. Below the fold, a front-page photo and headline caught his eye: John Steinbeck Dies Here at 66.

“Oh shit!” he said aloud.

A man turned to Matt. “You okay, buddy?”

Matt pointed to the paper. “Steinbeck is dead.”

“Yeah, so?” the man said.

Matt placed a hand over his heart. “He’s gone.”

He elbowed his way off the elevator and headed for the office where he worked as a runner for a well-credentialed Wall Street law firm. Bonded to deliver securities, he carried stock certificates, bearer bonds and other valuable papers from one financial institution to another all over Manhattan. Matt was the youngest in a stable of men who sat daily in the runners’ room, waiting for messenger assignments.

“You guys see the paper?” Matt asked as he stepped into the runners’ room.

The men in the room, mostly retirees doing messenger work for extra income, replied, “Hey, Matt.”

“Morning, Matt.”

“Steinbeck is dead.” Matt waved the newspaper at the room.

Leon, the oldest of the runners, sat erect, his lean legs crossed, blowing a wisp of smoke from the cigarette holder he held. “Good to see you, Matt. And yes, his death is clearly a loss.”

Matt hung up his coat and slipped on a tan office jacket.

The intercom announced. “You’re up, Lou.”

A middle-aged man grabbed his jacket and walked out to the dispatch desk.

“He’s my favorite author,” Matt replied to Leon. “I love his books.”

“You’re young enough to remember what you read in high school,” a runner named Daniel said. “I don’t remember any of that crap.”

Matt said, “My opinion, Steinbeck wrote better stories than Hemingway’s macho shit.”

“And clearer than the drivel Faulkner wrote,” Leon said.

Bernie, another runner, changed the subject. “I went to Greg’s funeral over in Jersey yesterday. Heartbreaking.”

“One more young man lost to a fruitless war,” Leon said.

Matt shuddered. “Don’t talk to me about Vietnam. It roils my gut more than last night’s chili.”

“I thought you had a deferral,” Bernie said. “You’re in college.”

“Barely,” Matt said. His eyes dropped. “I’m only going part time for my degree at NYU. It’s my Teaching Assistant job that’s keeping me out of the draft.”

A thirty-something runner re-directed the conversation again. “I almost skidded on the ice last night, driving my girlfriend home,” Tony said. “Cold as hell.”

Leon flicked the ash off his cigarette as he said, “I don’t think hell is cold, Tony.”

“You’re from Montreal, right, Leon? I bet it gets colder than the tits on a penguin.”

Matt chimed in, “Tony, penguins don’t have tits.”

“Yeah? You know that, how? You an expert?”

Matt said, “I read an article on the Antarctic in National Geographic.”

“Ha. Talk about tits. You buy the magazine for the pictures of naked native women.”

Dutch, the law firm’s building engineer, popped into the room at that moment. “You guys talking about tits again?”

Leon asked, “You keeping the secretaries warm, Dutch?”

“If only…” Dutch said.

“I was referring to the heating system,” Leon said.

The intercom squawked. “Breen, you’re up.”

Matt grabbed his coat and headed for the assignment desk. Harry Novak, the dispatcher, handed him a thick manila envelope. “This goes to midtown. Hustle. They’re waiting for it.”

Harry stood and pointed to a large subway map on the wall. “This is your station. Two blocks to the receiving address.”

Harry handed Matt two tokens out of petty cash.

On the subway Matt re-read the article on Steinbeck’s death. The family scheduled the funeral service for December twenty-ninth. In the city, at St. James Episcopal. Madison Avenue on the upper East Side.

I need to be there, he thought. A work day. I’ll call in sick.

After his delivery, on the trip back to the office, Matt spotted several young Marines in uniform waiting on the platform. He felt a fist twist his stomach. That could be me.

Most of the men were out on runs when he returned to the office. Bernie pulled him aside.

“When do you get your degree?” he asked.

“This June…on my twenty-fourth birthday.”

“And you wouldn’t be free of the draft till you turned twenty-six, right?”

Matt nodded. Rubbed his fingers together. Wiped his damp hands on his pants. “And the draft lottery starts next December. I can’t stop sweating this shit.”

“Go home tonight, have a cold beer, read a good book. Take your mind off this.” Bernie waved his hands at the room.

Matt closed his eyes, took a deep breath. Read a good book. Matt had read all of Steinbeck’s stories. He always felt disappointed that critics and writers did not give Steinbeck the credit and attention he deserved. Yes, he had a Pulitzer and a Nobel Prize for Literature. But scant attention when compared to Hemingway and Faulkner.

The ever-popular The Grapes of Wrath did not top Matt’s favorites list. A great story, sweeping in its scope, but for Matt, more a road trip story than a tale of social unrest. Families of farm workers traveling in dilapidated vehicles, held together by spit and wire. On the road seeking a better life.

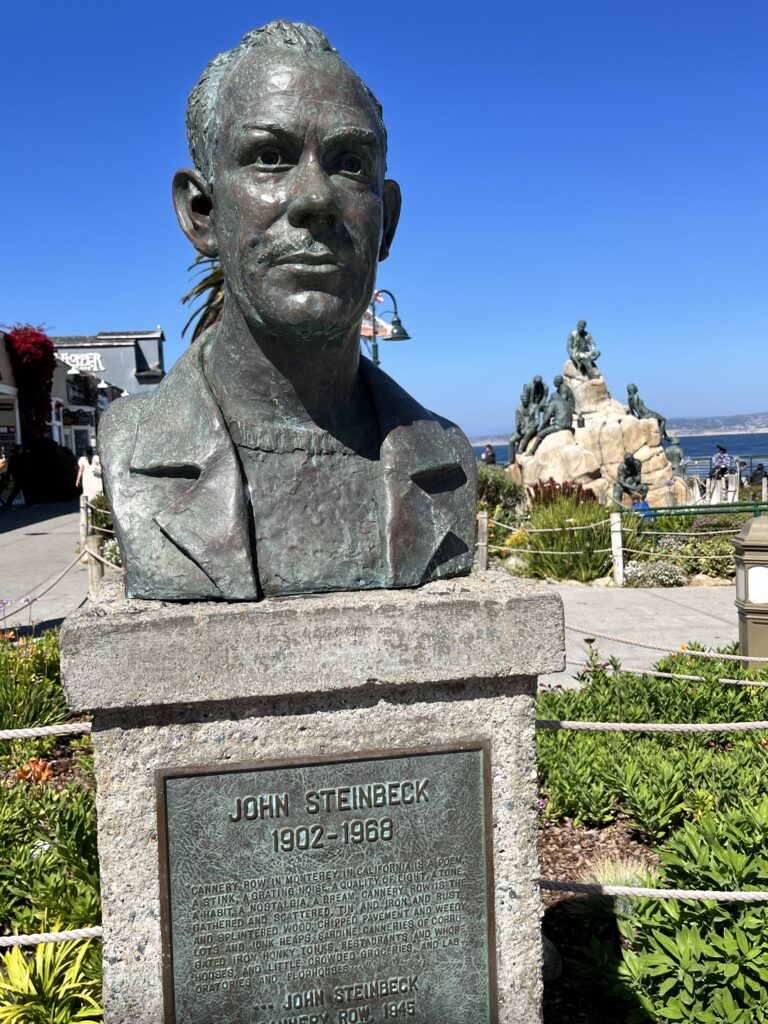

The characters in Cannery Row reminded Matt of the guys he sat with all day in the runners’ room. Not down and out, but scraping by. Looking for shortcuts. Sometimes crude, yet kind, almost lovable.

Bernie’s cough brought Matt back to the conversation. “Good advice, Bernie, but it won’t stop me worrying.” He glanced at Bernie. A lucky man, too old to face the draft. Matt felt himself teetering on a tightrope. His part time college work and TA job kept him out of the Vietnam draft. Barely. One of the young runners in his firm had been called up a month ago. The guy left scared shitless. Came home in a body bag. That was the funeral Bernie had attended.

Matt held Bernie’s eyes. “My buddies from the neighborhood and from school all have jobs teaching. That gives them deferrals. Me, I follow the news every night. Go to bed with a burning stone in my gut.”

Matt shrugged, pointed a thumb at himself. “I’m no teacher, Bernie. I’ll finish my degree in June, unless I get a draft letter before that. Then what ? A body bag with my name on it?”

After the holiday, on the morning of the Steinbeck service, outdoor temps reached only the mid forties. Matt dressed in slacks, a shirt and tie, a sweater. Added a trenchcoat and thin tan leather gloves. On the way out of his apartment building he ran into Joe, his neighbor in the apartment below his.

“Hey Matt. You going out?”

“No, Joe. Just walking the halls in my coat.”

Joe nodded. “Cute… Say, I can’t go out, what with my legs and this cold.”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“Can you pick me up a can of Spam and a box of Mac and cheese at the grocery store on your way back?”

“Joe, I’m running late.”

“Okay. Hey, you seen today’s paper. Big story on the draft lottery starting up next year. You gonna be okay?”

Matt shivered. “I hope so, Joe.” He turned to leave.

“Hey, you seen the super? I’ve been waitin’ a month for him to fix the leak in my kitchen faucet.”

“I know.”

“This guy is the pits. He’s fuckin’ useless.”

“I know.”

Joe rattled on and Matt felt like he said ‘I know’ a hundred times before he got out the front door.

The service at St. James Episcopal had already started when Matt arrived. All the pews were occupied. He found space to stand in the back. A speaker at the pulpit eulogized Steinbeck, reading from The Grapes of Wrath. A man standing next to Matt whispered in his ear.

“That’s Henry Fonda.”

In the room with a celebrity, Matt thought. Awesome.

At the end of the service, pallbearers shouldered the casket down the aisle. A white cloth draped the casket, fresh pine boughs on top. As the pallbearers reached the front doors, Matt inhaled the pine aroma. Maybe for the last time. He closed his eyes, shook his head.

The same man next to Matt leaned in and said, “I’m a Frenchman. If Steinbeck had been a Parisian, this church would have been packed. The whole city would have turned out to honor a writer.”

“Yeah, I hear you,” Matt replied.

As he moved out to the sidewalk, someone called to him. “Matt. Hey, Matt.”

He turned to see his TA professor from NYU. “Hi, John.”

“I’m glad to see you here, Matt. You really dig the significance of American literature.” He patted Matt’s shoulder. “That’s why you’re my TA.”

“Steinbeck has always been my first choice.”

“Hey, when winter break is over, Matt, we need to talk.” John shifted his feet, shoved his hands in his pockets. “Budget cuts are coming. I may have to drop you as my TA.”

Matt felt himself blanch. “Shit.”

“Yeah, ‘shit’ is right. It may jeopardize your status with the draft deferral. Not sure yet. I’ll have to talk to the dean.”

“Ah, man, this is not good.” Matt looked up at the cloudy sky.

John squinted. “Hey, relax. We can work something out. You’re a valuable asset in my class… I gotta run. We’ll talk next week.”

Matt shivered, wrapped his trenchcoat tightly around himself. He watched the mourners file out of the church. I’ll come back from Nam in a flag-draped casket and no one will come to my funeral.

On the subway ride back to Brooklyn, Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley swirled around in his head. Matt often dreamed of buying a truck, rigging it with a camper, and driving cross country. Driving free with no plans. But that would take money. Much more than his bank account would allow. However…if he did that, the draft board couldn’t find him. Disappear and ride free.

Back in his neighborhood Matt picked up the food items Joe had requested and got himself a couple of beers. He rang Joe’s bell.

“Hey, Matt. Thanks, man. You’re a standup guy. Can you come in for a minute?”

Matt stepped in. Joe had been watching a game show blaring on TV. He flipped it off.

“Sit.”

Matt found a comfy-enough chair. Sniffed what smelled like cigar smoke mingled with bacon.

“Matt, you look like shit. No offense.”

“None taken. Yeah, I feel like shit.”

“What’s up? Girl trouble?”

“I wish. You gotta have a girl to have girl trouble.” Matt told Joe what his professor had said about the TA job.

“Fuck the draft. Fuck the war. We need all you young guys here at home.”

“Thanks, Joe.”

“You’re a good neighbor. Quiet. The last guy upstairs was noisy as hell. TV blasting all night.”

Matt listened to Joe run on about all his woes. He finally excused himself, went upstairs and collapsed in his own apartment.

He popped open a beer, picked up his copy of Travels With Charley, and stretched out on his couch. The beer did nothing to calm his roiling gut.

The next morning, back in the runners’ room, Matt and Leon sat alone, all the other guys out on runs.

“Hey, Leon,” Matt asked in a low voice. “What’s it like in Montreal?”

“Bitter cold right now. But wonderful in the summer. Why?”

“I got a problem.”

Leon looked around the room, leaned toward Matt. “Tell me.”

Matt filled Leon in on his conversation with his professor and his tenuous draft position. He whispered, “I think I gotta run.”

Leon reached for a pad and pen, scribbled, handed it to Matt.

“Call this man. His name is Ray. Runs a settlement house in Montreal, in a poorer neighborhood. They serve hot meals, hand out clothes and shoes to homeless men. Tell him I referred you. He can give you a room if you help around the house.”

Matt looked at the paper. Freedom?

Leon went on. “Not a paying position, but Ray can help you find a job. You can save enough money to take the train cross country to Vancouver. Plenty of paying work out there.”

Matt opened his mouth to say thanks, but Leon cut him off. “Move on this. You can’t risk being called up. I’ll mail your last company check to the address in Montreal… And when you cross at the border, tell them you’re there for a few months as a volunteer. Part of your college work. Do not say you’re there looking for a job.”

Matt nodded. Whispered, “Thank you.”

The intercom squawked. “Leon, you’re up.”

Leon flicked ash off his cigarette holder. “Auvoir, mon ami.” He stepped out.

Two days later, on New Year’s Eve, Matt sat on a night train bound for Montreal. He carried a duffle bag with clothes, books and necessities. He had left his apartment with a month paid on his rent. No one would look for him there for a while. He had not said anything to his NYU professor. He had emptied all but a few dollars from his checking account. Told Joe to wait a few weeks, then help himself to anything in the apartment.

Matt disappeared without telling his buddies. Better they knew nothing about him being a draft dodger.

He stared out the window into the black night. As he rode north, the light dusting of snow in downstate New York gave way to piles of snow, wind-blown drifts, trees drooping with the weight of a wet snow. Ice crystals formed around the window edges.

The train carried Matt deeper into a bitter winter. He shuddered. This is no Steinbeck itinerary. No truck. No dog. The clack, clack, clack of the train wheels began to ease the stone in his gut. He squeezed his eyes tight when images from the movie King Kong crossed his mind. Elevated subway riders staring out into the night, coming eyeball to eyeball with Kong standing next to the el. A routine ride home morphed into a tragic encounter with a giant gorilla. Matt eyed his reflection in the window. I think I dodged my own gorilla.

Matt pulled a notebook and pen out of his duffle. He jotted the beginnings of a journal. Notes on a new life. A new country. A tarnished country left behind. Unable to return without possible arrest.

A passenger stumbling down the aisle made Matt think of the Okies in The Grapes of Wrath. They traveled in desperation, looking for better jobs, money, housing. He felt the desperation in his own soul. Forced to leave his life behind. Running from a fruitless war. A war old rich men sent young men to fight.

Unlike the Okies, his journey would not include a lush green California. No, only snow and ice. And the hope that the rock in his gut would dissolve. The fear and dread would melt.

Matt caught himself laughing quietly. This could be the start of a new book. Travels With Matt. Leaving from New York, like Steinbeck. Heading north instead of west. Leaving not to see if the country he loved had changed. Matt knew damn well it had changed. And the change could easily have forced him to face fire fights in a steaming jungle and a return trip in a body bag.

As the train roared deeper into the frigid night, feeble horn toots announced midnight and a new year. A fellow passenger sitting with his wife and son reached across the aisle, shook Matt’s hand. “Happy New Year, pal!” Matt smiled at the greeting. A warm handshake on a cold black night. He took a long deep breath. I’m on my way.

***

Recent Comments