Mannequin Monday – What Lasts?

“How does your work affect the world?” Writer and marketing coach Dan Blank asks us to consider on this Mannequin Monday: “What will people remember of your writing?”

And I suggest that one lyric of songwriter Leonard Cohen offers a perspective on a writer’s impact.

Finally, I share an excerpt from an article I wrote for educators on the enduring work of journalists in combat and civil unrest zones .

This Week’s Story

For a number of years, I have been following Dan Blank’s inspiring body of work on helping writers/creatives connect with their readers and find an audience. In one of his blog posts from 2012, Blank invited us to think about the true impact of our creative work. His comments are just as fresh today.

Blank said, “I work with writers, and my particular focus is on developing a long-term writing career. Sure, I focus on marketing tactics that people can use today, and on book launches, social media, audience growth, etc. But what will people remember of your writing… years from now?”

He continued, “People talk about an author platform in funny ways. They talk about blogs. And Twitter. And marketing funnels. And email lists. They talk about 99 cent ebooks. And Goodreads.

“And while these things are elements that support the platform, they are not the platform itself… The effect you have on others is the platform. The meaning and purpose behind your work is the platform. The information you share that reshapes someone’s understanding is the platform. The story that inspires and opens new doors – that is the platform.”

The effect you have on others is the platform.

“The platform is the moment of connection that you can hardly put your finger on, and lasts in our memories, unconscious and worldview long after we experience it.”

His post concludes: “How does your work affect the world? Not because it was on some best seller list; not because you have 20,000 Twitter followers; not because your blog post got 50 comments; not because your book trailer went viral.

“What lasts?”

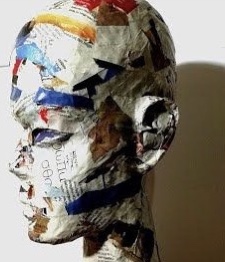

Indeed, what lasts? For a creative, what I think lasts is an elusive something you may never know, may only sense, may merely hope to achieve. It is that moment of connection that Dan Blank speaks of. We write to bring our characters to life. To give them the freedom to speak, to dare, to dream, to make mistakes. We sculpt to shape a form that speaks to those who look at it, who study it. We sketch or paint or film to bring joy or truth to the eyes of viewers. In the end, it is story that achieves that moment of connection.

But how does our storytelling live, endure? It’s easy enough to say, let our storytelling speak truth. Let our work touch a universal nerve. Not so easy to accomplish when we are struggling to articulate an emotional moment.

Dan Blank’s thoughts on how our work endures put me in mind of one of songwriter Leonard Cohen’s lyrics: “Busted in the blinding lights of closing time.” Perhaps a grittier way of saying the same thing. We labor to tell our stories, we create, we live, we seek relationships…but when the lights flare up at the end of our night, we are all busted. Illuminated by the end of our run, the end of our creative juices. The venue throws light on who we are, what we did, the real me trying to relate to, make connection with, others. We have perhaps been less than authentic when the lights are dim. We may have tried to fool ar least some of the time. And we have certainly tried to shed a ray of our own light in the dark of our venue. And then – blam! – the lights are up. I repeat Blank’s question – what lasts? What does our story look like when the lights come up?

We creatives won’t wait for the blinding lights of closing time. We can’t tell how we will be perceived. But we try to tell our stories in whatever light the venue gives us at the moment.

My Own Writing

Eight years ago I wrote an article titled “Truth Seekers: Journalists in Combat Zones.” The article is intended for educators to use with students in the classroom, to enhance understanding of how journalists from WWII until now reported from areas of combat and civil unrest. While not fiction, it is perhaps an example of enduring work by writers. Here is a short excerpt highlighting the work of Robert Capa (WWII) and Catherine Leroy (Vietnam War).

World War II – Robert Capa

In 1944, after three years of war, Americans were growing weary. They were anxious to hear that the war may be coming to an end. Rumors circulated of a huge assault on the German forces in France.

Allied Forces crossed from England to the beaches of France on D-Day, June 6, 1944. You may have seen the opening sequence of the film Saving Private Ryan, a horrific scene as Allied Forces fought to get off their boats and onto the beaches at Normandy while under enemy fire. A Hungarian photojournalist named Robert Capa struggled onto the beaches with the troops, capturing over a thousand pictures of the nightmarish scene. Unfortunately, a later processing error destroyed most of his negatives. Only a few shots remain.

Capa survived the beach assault, and went on in later years to photograph conflicts in other countries. The Capa Award was created in his honor. A source of inspiration to many journalists, he is famous for saying: “If your picture isn’t good enough, you didn’t get close enough.”

Vietnam – Catherine Leroy

About 20 years after World War II, the United States was engaged in another war, this one in Vietnam. The United States committed itself to supporting the South Vietnam government in Southeast Asia against the onslaught of Communist North Vietnamese forces. This war, too, was fought on foreign soil. And while far fewer American soldiers were involved, the public still wanted to know what was going on.

Catherine Leroy was only 19 years old when she first traveled to Vietnam to photograph the war. She carried a small Leica camera and spoke no English. Leroy learned English from the soldiers. She was wounded once while on patrol. She was even captured at one time by the enemy forces, but managed to talk her way into being released. She went on to cover other wars and civil conflicts. Leroy published a book on her experiences: Under Fire: Great Photographers and Writers in Vietnam.

The National Press Photographer’s Association says, “When she was much older and reflecting upon her career Leroy said in an interview that as a child, ‘Photojournalists were my heroes. When I looked at (magazine) Paris Match as a girl, to me that was an extraordinary window to the world.’ Influenced by the magazine’s strong photojournalism and images of conflict on its pages, Leroy knew even then that she wanted to photograph war. And there was one going on at the time, in Vietnam.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, the news media extended beyond newspapers to include television and news magazines. Reporters in Vietnam now regularly carried still cameras as well as notebooks. They traveled with the U.S. troops through the jungles of Southeast Asia, again suffering along with the fighting troops. Vietnam is a subtropical land, humid, rainy, hot, much overgrown with jungle.

America wanted to know how its troops were faring there. Some citizens wanted to know why the United States was there in the first place. Protests against the war were common. US military assessments painted a positive picture of American progress and enemy losses in Vietnam. As the war progressed, some reporters began to challenge this assessment.

On the Old Dominion University website, Joyce Hoffman writes that “Vietnam was the most accessible war in American history for reporters of either gender. Women had few problems acquiring accreditation. The press had never before had such complete assistance in covering any other military conflict. Until 1965, America continued to insist that its role in Vietnam was purely advisory. To have restricted the press or imposed censorship of any kind would have signaled that the Army of South Vietnam was receiving something far more serious than advice.”

No war was ever photographed the way Vietnam was.

(See a 2005 taped interview with Catherine Leroy and several other war journalists and photojournalists. The interview and discussion includes a brief slide show of the history of war photography. Viewer discretion is advised, since some of the images could be disturbing.)

Hal Buell, who ran The Associated Press photo service for 23 years, says the Vietnam War was a turning point for war photographers.

“No war was ever photographed the way Vietnam was, and no war will ever be photographed again the way Vietnam was photographed,” he says. There was no censorship. All a photographer had to do, says Buell, “is convince a helicopter pilot to let him get on board a chopper going out to a battle scene. So photographers had incredible access, which you don’t get anymore.”

***

Leave a Reply